EVANESCENT

We gathered in common, familiar places.

I could give them a face, a name, or a story

if that writes pages of a memoir or makes a poem.

I could mention the fire and rain of our years.

Truth be told, many of them have passed. Like me,

the ones living are slowly dying of something,

seldom calling or sending messages to each other.

I say I understand and move on to another day,

meeting, greeting, and talking to people

who can never make the ripples that innocence

made of pebbles skipping across muddy ponds,

boys creating moments wildly in the crosswalks

of meandering paths, when we gave no thought

to memories that would suddenly vanish.

PIGEON-TOED DANCE

for Charles Roland Floyd

One day I invited Charles to come over.

We didn’t talk much. Watched cartoons,

laughed, and wrestled on my bedroom rug.

Later, I found my piggy bank half-empty.

That was fourth grade with Ms. Conway,

the cowhide strap every student dreaded.

Too slow to learn, Charles was sent back

to second grade, where he dropped out.

His tongue was tied with square knots,

English that slurred and sounded foreign.

Couldn’t pronounce proper names, read

or write, but always won in nickel tonk.

Had the rhythm of a white house party,

tripping on his tangled, pigeon-toed feet.

On Legion Field, he never got a handoff,

a pass thrown or a tackle but he played.

Years later, he got a job nailing pallets.

Cool, I thought. Charles making money,

wearing new shoes, and putting coins

toward cigarettes and cheap port wine

those nights we rolled blunts, squatting

on crates behind the white man’s store

where black folks bought groceries.

Then, the break-in for a car CB radio

that never played again. Alone, Charles

shot dead by a black cop. No memory

of his face, only the Creole complexion

and fine curly hair, his palsy moves

and speech, and that silly, jerky laugh

that seldom scatted with the beat, only

a dear friend who, in all his brokenness,

was as human and loving as each of us.

LOST POEM

for Victor Hebert

The last time we talked was days before Christmas.

You had remarried and business was doing well.

Looking like a Black Santa with your round belly,

burly beard, and big gap-tooth smile, you bore

an armload of gifts for Narva, the kids, and me.

In your thirty nine years, you gave me that one gift,

unboxed, poorly wrapped, and without a bow,

so small that I placed it on a shelf above my dresser.

One July morning I got a call saying you had

a massive, fatal heart attack, the way your father,

my grandfather, had fallen fifteen years before.

In days that followed, a part of me left this world.

A song, “The Rose” by Bette Midler, kept me

from overdosing or putting a bullet in my head.

I looked above my dresser mirror and found

a handkerchief inside a tiny, unopened package.

Streaming tears, I recalled the Christmas Eves

we stood in long lines with other poor children

to get candy and toys from Sheriff Deputies,

not knowing we were poor. I wrote my first poem,

not thinking it was a poem. In time, I lost those

feeling words and never tried to rewrite them,

until thirty years later, as I gaze into an abyss

and see them by the firelight of your good heart.

Poet’s Statement

As someone who has a passion for nostalgia, I hold on to old things, personal artifacts one might say, that connect me to my past life. I also cling to memories of people I’ve known. But I’ve learned that not everyone cherishes “the good old days.” The older I grow, the more distance I find between and among individuals I grew up with or worked with over the years. For whatever reasons, many of them would rather put the past behind them and not look back. I think and feel differently. Through the lens of the past, I see and understand the present more clearly and discover more of the individual I am becoming.

In my seventy-one years, I’ve made many endearing acquaintances, some more personal and memorable than others. The poems written for this issue of the journal are about several of those people and experiences. In subtle ways, they say as much about me as they do about the people I wrote about. Each poem speaks to the meaning and experience of camaraderie in a distinct and nuanced way.

“Evanescent” reflects on my boyhood days and how fleeting the memories of those experiences become over time. They are reflections that personify the truth that the older and wiser we grow the more sheltered and solitary our lives become. More often than not, memory of the innocence and spontaneity of our childhood dies, not by loss of memory but by distance and lack of personal interaction. We choose to not remember.

“Pigeon-Toed Dance,” is about Charles, a close friend of my childhood and young adult days who was physically and mentally challenged. Charles might not have been the first child I knew who had a disability, but he was the first and only one I befriended. The experiences we shared and his untimely death left an indelible impression on me. In the poem, I not only wanted to humanize Charles but to fully bring him to life, thus the details that paint a portrait of him, more for my nostalgic nature than for the reader.

Originally titled “Last Christmas,” the poem, “Lost Poem,” was literally lost for nearly thirty years. I wrote it in 1994 while grieving the sudden death of an uncle who was more like a younger brother. I never tried to rewrite those words until the moment I sat to recount the details of that painful experience. The poem was “found” in the moment of its re-creation. Such is the power of poetry. “Lost Poem” was the very first poem I wrote, though “not thinking it was a poem,” and the beginning of my journey of becoming a poet.

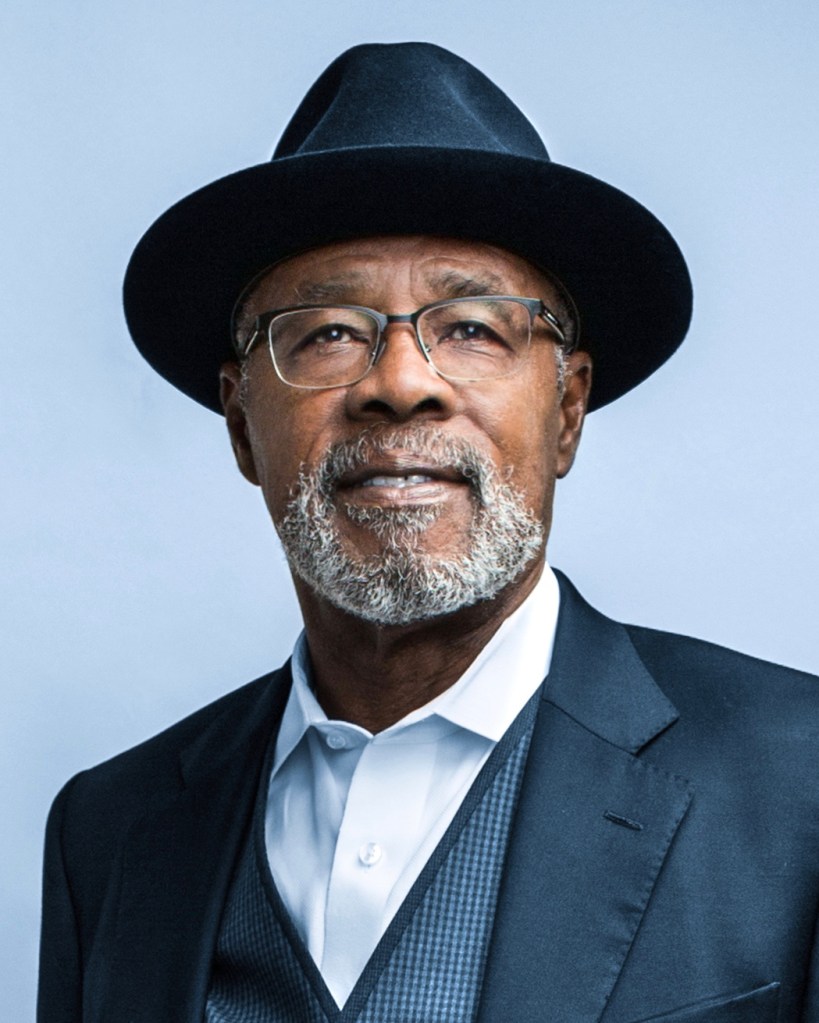

John Warner Smith was the Poet Laureate of Louisiana from 2019 to 2021. Smith has published five collections of poetry, most recently Our Shut Eyes (MadHat Press, 2021). His poems are widely published in literary journals across the country. Smith’s novella, For All Those Men: When the KKK Threatened to Take Control of Louisiana, was published by UL Press in November 2022. A Cave Canem Fellow, Smith is also a 2020 Poets Laureate Fellow of the Academy of American Poets and is winner of the 2019 Linda Hodge Bromberg Literary Award. He earned his MFA at the University of New Orleans.